Though many mobility management strategies have been proven to be effective, too often successful programs are grant funded and disappear when grant funding expires. It is therefore essential that program leaders strategically use evaluation data and findings that have appeal to potential funders.

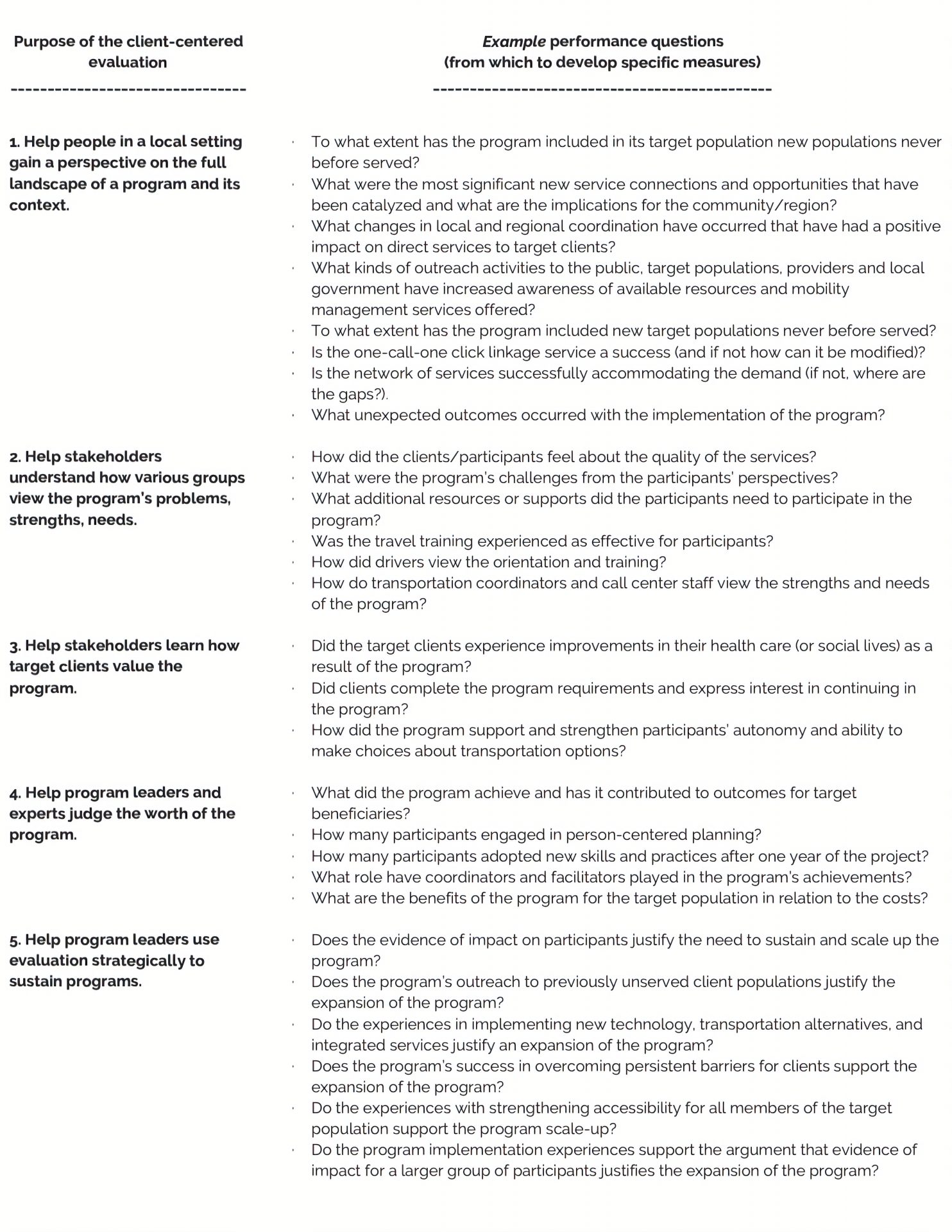

Client–centered evaluation requires that the people who are implementing, funding and using the programs are heavily involved in interpreting and using the findings to improve their processes, understanding, and decisions for the future.

References

Bloom, M. (2010). Client-Centered Evaluation: Ethics for 21st Century Practitioners. Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, Volume 7, Number 1. White Hat Communications.

Mitch, D., Claris, S., & Edge, D. (2016). Human-Centered Mobility: A New Approach to Designing and Improving Our Urban Transport Infrastructure. DOI: 10.1016/J.ENG.2016.01.030

Rahman, M.M., Deb, S., Strawderman, L., Smith, B., & Burch, R. (2019). Evaluation of transportation alternatives for aging population in the era of self-driving vehicles, IATSS Research, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iatssr.2019.05.004

Spiegel, A.N., Bruning, R.H., Giddings, L. (1999). Using Responsive Evaluation to Evaluate a Professional Conference. Educational Psychology Papers and Publications. 183. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/edpsychpapers/183

Stake, R.E. (2010). Program Evaluation Particularly Responsive Evaluation. Journal of Multi-Disciplinary Evaluation, v. 7, n. 15, p. 180-201. Accessed 2/27/20 from http://journals.sfu.ca/jmde/index.php/jmde_1/article/view/303

Stufflebeam, D. (2019). New directions for evaluation. No. 89, Spring 2001. Jossey-Bass.

Stufflebeam, D.L., & Madaus, G.F. (Eds., 2000). Evaluation Models: Viewpoints on Educational and Human Services Evaluation. T. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Carol Kochhar-Bryant is an Evaluation Consultant with the National Center for Mobility Management, and Professor Emeritus at the George Washington University, Washington D.C. She lives in Reston, Virginia.